The Shadow of

Oru Palace

pigment prints, mixed media, site specific installations

2022

<

>

The site-specific exhibition observed a space in Oru Park near Toila parish from the early 20th century to the present day. Unfolding through three floors, the visual narrative was both a chronological story and a photographic research. Viewing the former location of Oru Palace as a place of remembrance, where memory and history intersect, the exhibition told the story of Oru Palace as a symbol whose history casts a shadow on the events that followed the palace’s destruction. By Introducing the diversity of narratives related to the former location of the palace and their communal impact, the exhibition explored various contemporary ways of remembering that influence the symbolism and purpose of the space.

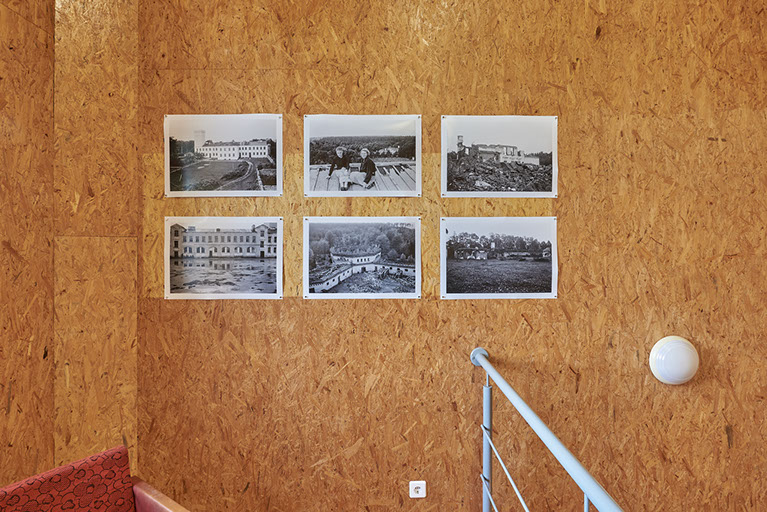

The exhibition took place in the tower of Toila parish’s school building, which is the only remaining architectural structure of the former Oru Palace complex. The exhibition featured photos, texts, and objects that examined the history of the place. The photos were selected images found in different memory institutions' collections, as well as in the archives of the local community and the author. The first floor of the exhibition covered the period from 1898 to 1944, with photos depicting the palace and its surrounding park as an exclusive location. The second floor introduced the Soviet period, the events following the destruction of the palace, and school life, giving the space a more collective dimension. The third floor of the exhibition presents the post-independence and contemporary surroundings of the palace grounds, exploring the pluralism of the place's use and lived experiences. The exhibition is not a comprehensive or exhaustive historical study but rather a research project that offers different ways of engaging with the history of a place.

Exhibited in Toila Gymnasium, Toila parish, Estonia, 21.08–18.09.2022

Graphic design and research: Maria Muuk

Short history of

Oru Palace

In 1897, Russian merchant Grigori Jelissejev purchased the Pühajõe Manor, its cattle farm (Föhrenhof), and the land of two farms next to the future palace (approximately 140 hectares) in the Toila area to build a summer residence. The estate, known as Jelisejev Palace, had 57 rooms and a three-story building. It was soon renamed Oru Palace and was completed in 1899. The complex included a decorative garden, a winter garden, terraces descending towards the river, a boat bridge, a riding arena, and horse stables. The park covered about 100 hectares, with a significant portion designed in a natural style by Georg Kuphaldt.

After the Bolshevik October Revolution, Jelissejev left for Paris, naturalising in France, and the palace fell into disrepair. In 1934, Estonian industrialists purchased the palace complex from Jelissejev for 100,000 kroons and gifted it to the Estonian state for public use. Jelissejev was unwilling to sell the palace to a private individual, insisting on selling it only to the state. Renovation work lasted until 1936, and the palace became the summer residence of the Estonian head of state at that time, Konstantin Päts.

In 1941, retreating Soviet troops set fire to the palace, causing extensive damage. The ruins, which housed a mine depot, were blown up by German forces in 1944. During the Soviet era, Oru Park became Toila-Oru. The park belonged to the Kohtla-Järve green belt forest management. In the 1960s, efforts were made to restore the park. Ruins were removed, terraces and stairs were renovated, the Silver Spring Cave (Hõbeallika koobas) was reconstructed, and an open-air stage was built.

In 1956, the former servants' house and the barracks building from the Estonian Republic era began to be converted into a school building. In 1957, an elementary school started in the building, later becoming a secondary school, and in 1998, it was named Toila Gymnasium.

In 1997, a landscape protection plan was developed, giving the park back its historical name, Oru Park. The landscape protection area was established to preserve the park's historical value and diverse terrain. Since 1997, an event called "Oru Park Promenade" has been held in the palace square and park every August. During the period of restored independence in Estonia, the park has been diligently restored. Recently, the municipal leadership has shown interest in restoring the former greenhouse and the palace.

Memory Place and its Representations

There are "lieux de mémoire," sites of memory, because there are no longer "milieux de mémoire," real environments of memory.

— Pierre Nora¹

Under the influence of memory, physical space transforms into an abstract place. Memory—whether personal, collective, or inherited—is constantly shaped by history and always influenced by the prevailing ideology. French historian Pierre Nora has written that places of remembrance can be material, symbolic, and functional, characterised by ritual, collectivity, and sacredness.² I am interested in how the former location of Oru Palace functions as a place of memory. By exploring the history of Oru Palace and contemporary activities around its former location, this exhibition uses photos, moving images, and objects to speak about Oru Palace as a lieu de mémoire. While creating the narrative, I have mainly focused on photographic activities aimed at depicting Oru Palace or its former location.

It is crucial to be aware of the role of photographs as tools of representation. Liz Wells has written that, contrary to looking, which is physically limitless, the photograph defines, frames, and imposes a specific way of seeing. "The image is a statement of what was seen. [...] Photography significantly contributes to our sense of knowledge, perception and experience, and to (trans)forming our feelings about our relation to history and geography and, by extension, to our sense of ourselves."³ Therefore, the photos in the exhibition should be viewed while being conscious of both one's own position and the position of the photo's author. Additionally, it should be considered that the exhibition of photos as documents or works of art is deliberate and charged, and the created visual narratives are provocative actions by the author. Archives are also functional places of memory, and the material found in archives serves as the foundation for writing and depicting history. Therefore, it is important that the archival material related to a specific place is as diverse as possible. Materials found in large archives tend to support more of a "grand historical narrative" and may overshadow the diversity of historical experiences in one place. Eléonore de Montesquiou has written about the diversity of visual material as follows: "Switching between contemporary images and archival footage enables us to notice the continuity necessary to understanding the current paradigm, reading the present with respect to the past."⁴ Hence, it is essential to also rely on archives formed outside memory institutions. Social media and community archives can act as counter-archives, exposing the plurality of experiences existing outside the "grand narrative" and telling stories that have so far remained undocumented. In preparation for the exhibition, I have worked through virtual databases of major Estonian memory institutions, collected photos from the Toila municipality community, and explored how experiences in the former location of Oru Palace and its surroundings are represented on social media.

Aerial photo of the Oru Palace complex

Author unknown. 1930-1935

KLM FT 1034:1/167 F. Estonian War Museum - General Laidoner Museum

Aerial photo of Oru Palace complex

Author unknown. 1936

EFA.67.4.1360. National Archives of Estonia

Oru Palace as a Symbol

Oru became the beautiful facade of the Estonian state.

— Hent Kalmo⁵

After the October Revolution, Grigori Jelissejev emigrated to France, leaving Oru Palace and its park neglected. When Estonian industrialists gifted the palace complex to serve as the president's official residence, the complex was renovated to represent the institution of the Estonian presidency. President Päts himself played a leading role in the development of the palace complex. Oru Palace existed as the presidential residence for only four years, yet this brief period has become the most vivid era, strongly influencing the memory of the place today. To understand this, one must examine President Päts and the national trauma that struck Estonia at the end of the republic.

Oru Palace, view after reconstruction

G. V. Baranovski. 1936

EAM Fk 6736. Estonian Museum of Architecture

Hent Kalmo, in his analysis of the figure of Konstantin Päts, writes: "Oru – this is the place we must start if we want to understand Päts's character."⁶ In the context of the authoritarian "Era of Silence," Kalmo sees the Oru Palace complex as Päts's vision of his ideal Estonia. The gardening propaganda that began in the Era of Silence foresaw the beautification of Estonia. Kalmo refers to this as "aesthetic compulsion": "Aesthetic compulsion stems from the vision of the whole picture: the more beautiful the whole, the greater force it exerts on blemishes because stubborn discord is marred by greater beauty. Looking from a hill and admiring the homeland, a single dilapidated house can spoil everything."⁷ Authoritarian order is capable of significant reforms and actions, but at the same time, it suppresses the diversity of opinions and their impact. Therefore, Oru Palace can be viewed as the facade of authoritarian Estonia, representing the ideological legacy of the Era of Silence. Looking at photos and postcards preserved in archives and museums from Päts's time at Oru Palace and considering Kalmo's interpretation of Päts, one can find a similar mood in these photos. The photos depict the palace as a sculptural form, captured from a low angle, towering and adorned with beautiful gardens. Most photos are devoid of people, and if individuals are present, they appear as guests, tourists, onlookers, or employees. These photos suggest an elitist and idealistic space. In such photos, there is a distance that invites admiration but from afar. Although the palace was open to visitors when the president was not present, it was still a private space onto which various desires could be projected.

A group in Oru Park, Oru Palace in the background

Author unknown. 1936-1939

EFA.706.0.338662. National Archives of Estonia

The former location of Oru Palace is no longer physically obscured by the palace itself. Oru Palace no longer exists, but the memory of it as a symbol is deeply ingrained in community and national memory. The national image of the lost palace, its connection to occupations, and the traumas associated with them evoke various nostalgias, which, in turn, serve as catalysts for different events and rituals related to the palace as a memory place today and in the future. The ideal image of Oru Palace still exists in both how it is portrayed and how it is spoken about. The symbolism of Oru Palace as a memory place is strongly influenced by its physical cessation and the end of independence – occupying military forces destroyed the palace during a period when Estonia lost its independence, and the country was governed by foreign ideologies. In the context of independent Estonia, the symbolism of the long-lost Oru Palace can now be viewed nostalgically. Ene Kõresaar, analysing the Estonians' nostalgia from a biographers’ perspective, treats the occupation period as a disruption: "The 1940s disruption becomes a dominant narrative scheme in the 1990s, or rather, in its first half, for talking about the history and biographies of Stalinism era, containing 'ready-made' assessment patterns and meanings for this period. The main themes of the 1940s disruption are the destruction of the symbols of national independence by the Soviet occupying authorities. It is an experienced cultural conflict expressed, on the one hand, in the fragmentation of national unity (the emergence of an Estonian 'red' or collaborator in biographies) and, on the other hand, in the popular construction of the Soviet power's cultural, mental, and ideological unacceptability to Estonians."⁸ Today, the events around the Oru Palace square are also characterised by the impact of a disruption. Nostalgia is strongly linked to memory and its narratives, and it can be described as a longing and yearning for a lost time. Nostalgia is a human reaction to engaging with and remembering an imagined past. Therefore, I do not consider nostalgia inherently negative, but the ways in which nostalgia is practised can influence the interpretation and discussion of the past in the present and in the future. In the following, I will examine the ways in which nostalgia is practised around the former location of the palace and its surroundings.

Oru Palace. Burnt. A soldier stands next to the sculpture in front

Author unknown. 1942-1944.

RM F 1505:11. Virumaa Muuseums

Oru Palace ruins

Märt Mõtuste's photo archive

Toila municipality library collection

Practices of Remembrance

Cultural theorist and media artist Svetlana Boym has proposed a typology through which various forms of nostalgia can be identified: restorative and reflective. "Restorative nostalgia puts emphasis on nostos and proposes to rebuild the lost home and patch up the memory gaps. Reflective nostalgia dwells in algia, in longing and loss, the imperfect process of remembrance. The first category of nostalgics do not think of themselves as nostalgic; they believe that their project is about truth. This kind of nostalgia characterises national and nationalist revivals all over the world, which engage in the antimodern myth-making of history by means of a return to national symbols and myths and, occasionally, through swapping conspiracy theories. Restorative nostalgia manifests itself in total reconstructions of monuments of the past, while reflective nostalgia lingers on ruins, the patina of time and history, in the dreams of another place and another time."⁹ If restorative nostalgia treats the past and its restoration as true, reflective nostalgia approaches it ironically and acknowledges that the object of nostalgia is time, not space.

I was inspired to embark on this project by an article in Maaleht published in 2018, where Toila municipality mayor Eve East discussed potential plans for rebuilding Oru Palace. Starting with the statement "Oru Palace must be rebuilt,"¹⁰ East describes a larger plan, where a monument to President Päts is first created, then the former greenhouse is restored, and finally, ways to reconstruct the palace are being explored. Today, a statue of Päts, created by Seaküla Simson, stands on the palace square, and the detailed planning of the greenhouse is in progress.¹¹ Different articles on the restoration of Oru Palace suggest that complete restoration is not planned, as it may be impossible from the perspective of the Estonian National Heritage Board. East describes that "if we don't talk about the 100% restoration of Oru Palace but about reconstructing it, the hands can be freer, and the thoughts more ambitious."¹² Although the goals and functions of restoring and reconstructing buildings differ, it still involves the restoration of a lost symbol and covering up the ruins. Christina Cameron, a professor at the University of Montreal, writes in her article "Reconstruction: Changing Attitudes" that the positions of heritage conservation institutions are changing concerning the reconstruction of destroyed buildings. The post-World War II reconstruction project in Warsaw was justified by the possibility of collective healing from trauma.¹³ An argument against reconstruction could be that a new building erases established ways of talking about history and overwrites it. I am interested in exploring the values that rebuilding Oru Palace could recreate or erase and whose interests it serves. Rebuilding the palace, as a form of restorative nostalgia, romanticises 1930s Estonia and the Era of Silence. The danger is that local and contemporary community values might be lost, and the space might become exclusive once again.

"The Object of Nostalgia"

Aap Tepper. 2022

Next, I present two examples representing a more progressive form of reflective nostalgia. The first is the "Oru Park Promenade," organised annually on August 20th at Oru Palace Square since 1997. Guests are asked to arrive dressed in 1930s period-appropriate attire, gather at the palace square, and throughout the day, there will be events, concerts, and refreshments will be available at the cafes. This event, although inherently nostalgic, is aimed at the present day, as evidenced by the need to gather on the anniversary of the restoration of independence. The promenade is an event that creates a collective monument on the square, which could be called a "weak monument." Tadeáš Říha, Roland Reema, and Laura Linsi describe architectural forms that become monumental through collective will in their article "Weak Monument: Architectures Beyond the Plinth" for the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale Estonian Pavilion: "Sometimes it is the history, the location or the material that confuse the exceptional and the everyday architectural objects. In those moments, something odd occurs, not precisely in line with how the monument is traditionally understood."¹⁴ One form of a weak monument they highlight is ruins: "The ruin is not a finished product but a point of balance. Balance between rigidity of structure and the destructive forces of nature and man. Between the power that erects and the power that wants to take down."¹⁵ The ruins of the palace were almost entirely cleared, and today, the former palace location is marked only by the grass-covered palace square, the foundation of the former greenhouse, and the gardens that allude to the absence of the palace. Even emptiness can be a monument. Říha, Reema, and Linsi describe it as "charged void." "Regardless of a complete or partial absence, its position and location remain identifiable by adjacent spatial settings and through them the collective memory is kept alive. They mark a space open(ed) for negotiation, space which by that definition is truly political."¹⁶ The promenade is an example of how the rituals of gathering at the ruins intersect with the remembrance of the past and the appreciation of contemporary community values. The "charged void" of the palace square manifests in the symbolism of the memory place and provides an opportunity for discussions related to the rituals taking place there and future plans regarding possible reconstruction.

The second example of reflective nostalgia relies on a virtual time travel experience created by Estonian company Blueray at the palace square. It is an audiovisual stroll that can be experienced in the summer months at the palace square and its surroundings. Using VR glasses at different physical locations, visitors can see a 3D model of the palace complex, based on archival photos and drawings of the palace from the 1930s, accompanied by a storyteller's colourful narration about the history of the palace. Despite being intentionally nostalgic, this experience does not alter real space. At the end of the tour, it is possible to walk in contemporary space and experience the charged void. As a form of ruins, today's palace square functions as a public space and a progressive tool for talking about the past. It serves as a scar, the covering of which would clearly change the current function of the place.

Virtual tour "VR Toila 1938"

Aap Tepper. 2020

The Growth Space Around the Ruins

When we were in school, the palace ruins were still standing, and during drawing class, we used to sketch them.

— Talvi Vestel¹⁷

Even though this project is nostalgia-critical, I must admit that when talking about Oru Park, I am not impartial. For 12 years, a mesmerising road guided me through the park on my way to school. Toila is a place by which I position myself on the world map. This space is strongly charged with nostalgia for me. This nostalgia is not connected to Estonian history but with my childhood experiences. The park is a psychogeographic space for me, where places remind me of my school path and leisure time back then. After school, while walking home, my classmates and I often stopped in resting places, enjoyed the changing seasons of the park, and discussed everyday concerns and school events. Sledding and skiing down the slopes of the valley served as our northern ski resort and in the summers, we spent evenings until morning in the park. Every year, I try to take at least a week off to spend time in Toila, walking in the park and enjoying nature in the evenings. It is a place where I always feel safe because I know every corner of the park and can confidently traverse it even in complete darkness. For me, it is a public space that has taught me to appreciate and observe nature.

"Stargazing at the Palace Square"

Aap Tepper. 2015

The shadows of the historical narratives and occupations obscure the period when community life began around the ruins of Oru Palace. In 1957, a school was established in the former servant's house of the palace and the Oru garrison building. The building was renovated, and education life started inside, in the garden, and in the park. Next to the school, a pioneer camp started its activities in 1954, and later, a song stage was built in the park. Many people have written about education in Toila, including local historian Märt Mõtuste and longtime school director Olav Vallimäe, and Toila Gymnasium's memory books vividly narrate students' memories. In the archival databases there are very few photos depicting the Soviet period in Toila and it seems like a hidden era. This, of course, does not mean that this material does not exist. In recent years, together with Lea Rand, the director of Toila Vallaraamatukogu (local library), we have been collecting and digitising local photographic heritage. A successful discovery came in March of 2022 when former Toila Gymnasium teacher Laine Kreegimets and I delved into the cabinets of the Toila Gymnasium museum. There we found Märt Mõtuste's collection of negatives, which includes nearly 2400 photo negatives. This collection contained some glass plates and six medium-format film negatives, which captured scenes from the period of the president's palace. The vast majority of the photo collection consisted of 35mm black and white film negatives from 1957–1993. These frames expose views of the ruins of Oru Palace, the renovation of the school, and the first years of educational life. This photo material bears witness to an active school life and conjures up an image of a lively space that exists around the ruins.

View from the roof of Toila school. Oru Palace ruins in the background

Märt Mõtuste's photo archive

Toila municipality library collection

Students skiing. School in the background

Märt Mõtuste's photo archive

Toila municipality library collection

In 2022, the school commemorated its 65th anniversary. Several generations have grown up around the ruins, and educational life is an important creator and preserver of community cohesion. The constant consolidation of national education into state gymnasiums poses a threat to a small school with significant community heritage. Toila Gymnasium students are fortunate that their school is located in such a picturesque place. Instead of navigating through the stressful city jungle, they have the opportunity to enjoy a meditative journey before classes, clearing their minds of everyday worries. I have asked my younger sisters, who are in primary school, to document their school journey, and the photos reveal the aforementioned experience. The observations of nature and pauses in different places indicate a curious gaze that values the environment around them. The pictures also show that schoolchildren traverse the park differently than tourists, using convenient shortcuts alongside the asphalted roads. These can be called "desire paths," born out of resistance to existing spatial logic. These paths are also monuments.

Early mornging on the schoolpath

Häli Tepper. 2021

"Desire Path"

Aap Tepper. 2022

In addition, the park proves itself as an effective public space in social media posts. Searching for the hashtag "#Orupark" on Instagram opens up an ocean of experiences. Captures of walks in the park, wedding photography, and shared experiences of promenade visitors emphasise a democratic spatial experience. Gradually, this visual material depicting the diversity of experiences also reaches the archives and quantitatively outweighs the documentation of Oru Palace. The community archive and social media posts act as a counter-archive, showing the functionality of the palace square as a memory place and public space. It is crucial that any future plans regarding this place involve this diversity of experiences and consider the aspect that the space around the Oru Palace square has been an important part of the community and has existed as a collective ritual and educational space way longer than the palace itself. A good example is already evident on-site. In 1997, the Nõiametsa pavilion near Oru Palace's garden was restored. The information board of the pavilion states that it was restored "according to the former floor plan but in an open form for public usage." The restoration process should be progressive and, in addition to looking back, take into account the present and also look to the future. If reconstruction it is essential, then, considering constraints and expert recommendations, the community should be consulted, and an inclusive outcome should be sought.

* Longer and edited version of this text was published in Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Volume 45, Issue 4, 2025 "Reworking the Eastern European Past through Audiovisual Archival Practices".

Photo series "Love Locks"

Aap Tepper. 2022

References

¹ Pierre Nora. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. – Representations 1989, nr 26, p. 7.

² Ibid. pp. 18–19.

³ Liz Wells. Land Matters: Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity. London: Tauris, 2011, Kindle edition, p. 6.

⁴ Eléonore de Montesquiou. Feodora, Olga, Sasha and Me. – Archives and Disobedience: Changing Tactics of Visual Culture in Eastern Europe. Edited by Margaret Tali and Tanel Rander. Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts Press, 2016, p. 186.

⁵ Hent Kalmo. Kadrioru aednik. – Vikerkaar 2021, No 3, p. 46.

⁶ Ibid. p. 47.

⁷ Ibid. p. 78.

⁸ Ene Kõresaar. Nostalgia ja selle puudumine eestlaste mälukultuuris: eluloouurija vaatepunkt. – Keel ja Kirjandus 2008, No 10, pp. 764–765.

⁹ Svetlana Boym. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2002, p. 41.

¹⁰ Rein Sikk. Toila vald soovib Oru lossi üles ehitada ja presidendile residentsiks pakkuda. – Maaleht, 14. November 2018.

¹¹ Sirje Sommer-Kalda. Toila taastab Oru lossi triiphoone. – Põhjarannik, March 10th, 2022.

¹² Rein Sikk. Toila vald soovib Oru lossi üles ehitada ja presidendile residentsiks pakkuda. – Maaleht, 14. November 2018.

¹³ Christina Cameron. Reconstruction: Changing attitudes, 2017.

https://courier.unesco.org/en/articles/reconstruction-changing-attitudes

¹⁴ Tadeáš Ríha, Roland Reema, Laura Linsi. Weak Monument: Architectures Beyond the Plinth. Zürich: Park Books, 2018, p. 9.

¹⁵ Ibid p. 13.

¹⁶ Ibid p. 14.

¹⁷ Toila Gümnaasium. Meie vilistlaste lood. – Toila valla lood VII. Jõhvi: TRÜKIS, 2012, p. 34.

^

© 2026